The Lure of the Archive: Life in the Margins

Wai Ho is a graduating English major at UC Berkeley. During the winter of 2016, she traveled to the Beinecke Library at Yale University to conduct archival research on Erasmus Darwin for a thesis. Her archival findings helped her develop her ideas on marginal discourse between unlikely speakers and addressees in botanical poetry and the personification of plant life. In Spring 2018, she will be studying abroad at Oxford University and conducting archival research at the Bodleian Library.

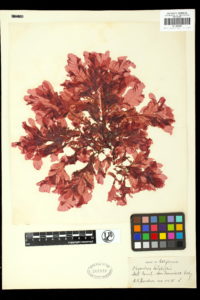

Archival research first lured me in with the promise of botany. In one sense, we could say that the very first texts came from the textiles woven from the fibers of plants. From the healers and botanists who touch, smell, and collect “green” organisms, we have insight into the behaviors and properties of plants. Plant life is interwoven into the lifestyles of Homo sapiens sapiens everywhere. The first archive to reveal this to me was Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, where I looked for ethnomedical and cultural uses of plant species in the oral stories of the Central Valley’s first residents. Later on, I discovered the University and Jepson Herbaria collections of preserved plant specimens. These pressed plants carry the traces of its former life rooted in the earth or ocean floor.

Archival research first lured me in with the promise of botany. In one sense, we could say that the very first texts came from the textiles woven from the fibers of plants. From the healers and botanists who touch, smell, and collect “green” organisms, we have insight into the behaviors and properties of plants. Plant life is interwoven into the lifestyles of Homo sapiens sapiens everywhere. The first archive to reveal this to me was Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, where I looked for ethnomedical and cultural uses of plant species in the oral stories of the Central Valley’s first residents. Later on, I discovered the University and Jepson Herbaria collections of preserved plant specimens. These pressed plants carry the traces of its former life rooted in the earth or ocean floor.

In the winter of 2016, I traveled to cold New Haven looking for plant life in yet another form. Had I been looking for plants in situ, this would have been a foolhardy endeavor—New Haven’s icy winter is hardly congenial to photosynthesis. But Yale’s Beinecke Library held the first- and second-editions of Erasmus Darwin’s The Botanic Garden, a two-volume poem on plant life. In addition, I came for a slice of Darwin’s late eighteenth-century literary culture, captured in 18th-century commonplace books, an early manuscript of The Botanic Garden, and Darwin’s correspondence with Anna Seward, a close friend and colleague of his.

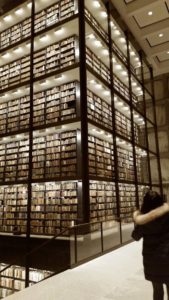

Entering the Beinecke Library, I could not help but feel a sense of awe. Thousands of books rise in a column of crystalline brilliance at the center of the library. It is easy to see why people call this display “The Tower.” The hallowed books of the archive are shielded and celebrated from a distance through thick glass. Less mediated by decades, if not centuries, of other critics’ handling the same texts, these archival materials encourage a fresh eye. At the same time, archival texts are also historical artifacts registering the time-driven decay and digestibility of paper and ink. Here in the archives, there is no Google Scholar, no zooming in on digital materials, just the fragile text and its mortal researcher.

Entering the Beinecke Library, I could not help but feel a sense of awe. Thousands of books rise in a column of crystalline brilliance at the center of the library. It is easy to see why people call this display “The Tower.” The hallowed books of the archive are shielded and celebrated from a distance through thick glass. Less mediated by decades, if not centuries, of other critics’ handling the same texts, these archival materials encourage a fresh eye. At the same time, archival texts are also historical artifacts registering the time-driven decay and digestibility of paper and ink. Here in the archives, there is no Google Scholar, no zooming in on digital materials, just the fragile text and its mortal researcher.

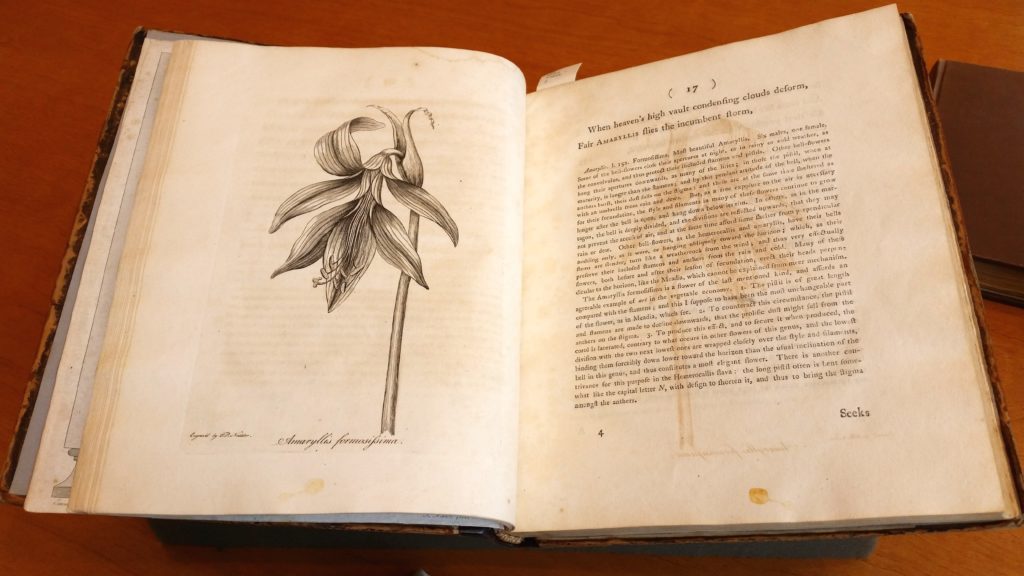

In the glassy terrarium of Beinecke’s reading room, I worked through Darwin’s effort to apprehend plant life with crystal clarity. Through the archive materials, I hoped to gain insight on the relationship between Darwin’s poetry and scientific writing. Both modes of writing proliferate in the space of The Botanic Garden: the poetry takes front and center while scientific footnotes dominate the margins of the page. What was so interesting to me about Darwin’s work is that he personifies plants as lively, flirtatious people and he does the work of the scientist by experimenting on plants as subjects of serious study. Without the footnotes, Darwin’s plant personifications are often puzzling, if not incomprehensible. Even a savant in horticulture would find it difficult to keep up with the interdisciplinary connections between a variety of sciences in The Botanic Garden. We readers thus look to the marginalia to be educated as we read his verses. With the earliest edition of The Botanic Garden before me, I realized the power of the humble footnote. I was able to examine not only the paratext of Darwin’s work, but the actual proportion of its placement for its first readers.

My interest in the spatiality of Darwin’s footnotes became an important part of my thesis, allowing me to work through the science of his botanical poetry in the marginalia and link it to the idea of the apostrophe, speaking to an addressee who is presumed absent or inanimate. Like the plant at the margins of our usual attention, the footnote draws our attention in a new way.

By bringing our attention to the footnotes, I want to value life at the periphery of our usual attentional practices, something that Darwin seems to be intensely interested in. Rather than centralizing what is marginal, the position of marginality actually implies information without making it propositional or declarative. This discourse that takes place at the margins of poetry allowed me to develop the concept of side-speaking to the readers, something I expand on in my thesis.

My dive into the Beinecke archives synapsed one more connection in the vast nexus of intertextual and scientific fibers of The Botanic Garden. Even after finishing my thesis on Erasmus Darwin’s lively personifications of plant life, I am still pondering how life in the margins might speak to us. I hope to continue this line of thought on my next archival trip to the Bodleian Library at Oxford University in Spring 2018.