From Walden to Winnie

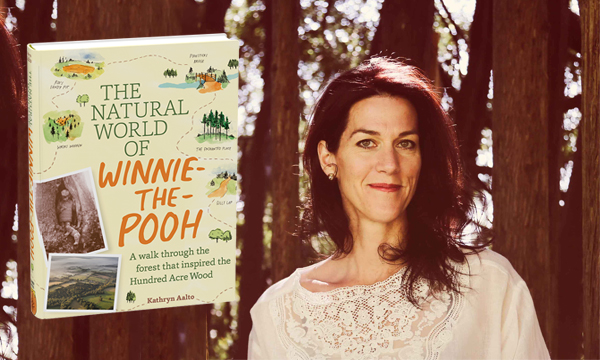

Kathryn Aalto (Cal English, ‘92) is the best-selling author of The Natural World of Winnie-the-Pooh: A Walk through the Forest that Inspired the Hundred Acre Wood (Timber Press), described by the Washington Post as a “lovely book” that “provides two great pleasures: a visit to the actual wild spots that inform the fictional Pooh world and a chance to slip into our memories of the books themselves.” A landscape designer, historian, lecturer and nonfiction writer, Aalto reflects here on how Cal shaped her as a writer.

Twenty-five years have passed since I was an English major at Cal.

In those days, a few students managed to creep to the upper floors of Sproul Hall with TVs tucked under their arms, then fling them through windows to the ground below while yelling, “Kill your televisions!” There were rallies, sit-ins, and teach-ins urging the Board of Regents to divest billions from apartheid South Africa. We saw the fall of the Berlin Wall. We saw Rodney King’s police beating, one of the first caught on tape. We saw the lone protester facing the tank on Tiananmen Square.

The time between then and now feels as short as the line on a child’s fishing pole.

World events from that time remain vivid, as do quieter moments that didn’t make headlines: mind-bending lectures from brilliant professors, sunlight streaming through Doe Library while absorbing a book, late night paper writing fuelled by Peet’s.

I remember vividly, too, how much I struggled to see the forest for the trees, as it were. There had long been a game of tug-of-war in my head between nature and culture, compounded by the usual 20 year-old English-major existentialism. There were so many options open but with book after book to read and paper after paper to write, sometimes it was difficult to see the big picture. I had always seen myself as a teacher and writer drawn to geography and the natural world, but my thinking about how I might personally bridge the gap got complicated, as it should, at Berkeley: Should I think about environmental law? Environmental journalism? Nature writing? Teaching? Even, landscape architecture?

I sought answers inside and outside Wheeler Hall.

A couple years teaching “The Amazing Brain” at the Lawrence Hall of Science confirmed my love of schooling. (Imagine: boa constrictors, warm bunnies, and even warmer school kids in one lab.) A dull stint at an Oakland law office axed law. An internship at a newspaper killed journalism but instilled a desire for true stories told well — a more personal and crafted storytelling hybrid-journalism that I would eventually define in graduate school.

And then, an unexpected way to see both the forest and the trees came into view. I noticed I was being shadowed by someone with big eyes, a pronounced nose and a 19th-century retro thing going on — and not just in one class but three.

I first caught sight of him across the room in Professor Donald McQuade’s course, “The Essay.” We studied essays ranging from Plutarch and Seneca to Woolf and Dillard — essays that ranged in tone from the high-flown to the informal — and discussed the traits of what I felt was an appealing and comfortable genre. A flexible genre, too: essays could be serious, logical, and dignified or lyrical, rambling, and personal, I learned. Having been a prolific letter writer, I felt essays — with the presence of a writer in the narrative — offered a way for me to be more personal with readers than journalism allowed. Essays were the right vessel for using fictional devices to make the nonfiction come alive with enhanced dialogue, a strong sense of place, and first-person narrative.

When the mystery man also showed up in Professor Mitch Breitweiser’s course, “The American Renaissance 1800-1850,” I got a little suspicious. I remember the proverbial moment I set eyes on him. Not only that, but I can recall where I was sitting in LeConte Hall and what I was reading. (Walden.) As Professor Breitwieser paced back and forth across the lecture hall explaining how wilderness, Walden, and transcendentalism made American literature distinct from British literature, I began to shake in my seat. I couldn’t hold my pen to take notes. It probably looked like I’d downed an octuple latte. At the time, it felt ridiculous and weird — a literary fit of sorts — but through Walden, the forest and the trees of my English undergrad days now didn’t seem so separate. From then on, I took every American lit class I could so as to understand what had shaped American writing.

The third course that helped shape me as a writer wasn’t actually listed in the English Department offerings in 1989. Called “Nature Writers,” it was a student-led course in the College of Natural Resources. Professor Emeritus Richard Feingold, then head of the English Department, asked me into his office to justify why it should count toward my major. I wouldn’t dream of responding: “Because maybe in a few years, I will be a New York Times best-selling author with what I can learn.” Still, he listened to my case and approved the course. Over in Hilgard Hall, it felt odd to study writing away from Wheeler Hall and my English tribe, especially when students shoved desks to the sides of the room to sit in a democratic circle on the floor. We were always covered in the dirt these future foresters carried on their hiking boots, but it felt apt given our study of nature writers such as Gilbert White, John Muir, Mary Austin, Rachel Carson, Gary Snyder, and dozens more.

You might be wondering if the gent was in this class, too. Yes, he was. Sitting cross-legged, right next to me. I finally turned to him and asked, “Who the hell are you?”

Well, not really.

And he couldn’t have answered anyway. He had never really been there; he had also always been there. It was Henry David Thoreau — essayist, naturalist, defining voice of the American Renaissance, father of environmentalism.

Since those undergrad days in Wheeler when the path through the forest and the trees was sometimes unclear, Thoreau has been a constant companion. Had someone touched me with a match when Professor Breitwieser explained Thoreau’s Walden, I may have gone poof! up in flames: maybe my 20 year-old self was stepping onto the next plane of her writing life. With one foot still in nature and the other in culture, I have a creative profession reading landscapes as texts, and a little more. I am a nature writer, landscape historian, and landscape designer. I teach critical thinking, creative nonfiction, and American literature of nature and place. Last year, I spoke in more than sixty American cities as a public speaker.

I was so honored when my second book, The Natural World of Winnie-the-Pooh: A Walk Through the Forest that Inspired the Hundred Acre Wood, climbed up the New York Times’ chart of best-selling travel books, was featured on National Public Radio, and was dubbed a People Magazine “Best New Book Pick” in nonfiction. It has been described as nature writing, a travelogue and a well-informed biography, and truly reflects all my nascent — near-flammable! — undergraduate interests during my days at Berkeley. (There are other exciting things happening with the book, too, though I can’t talk about them yet.)

A parting piece of advice: follow your own path, don’t be shy to ask for guidance, and remember to step back to see the forest…

***

Follow Kathryn Aalto on Twitter @kathrynaalto; for more information on her and her writing, visit www.kathrynaalto.com.

**Image credit: author picture (Emma Solley) and image of book (Timber Press)