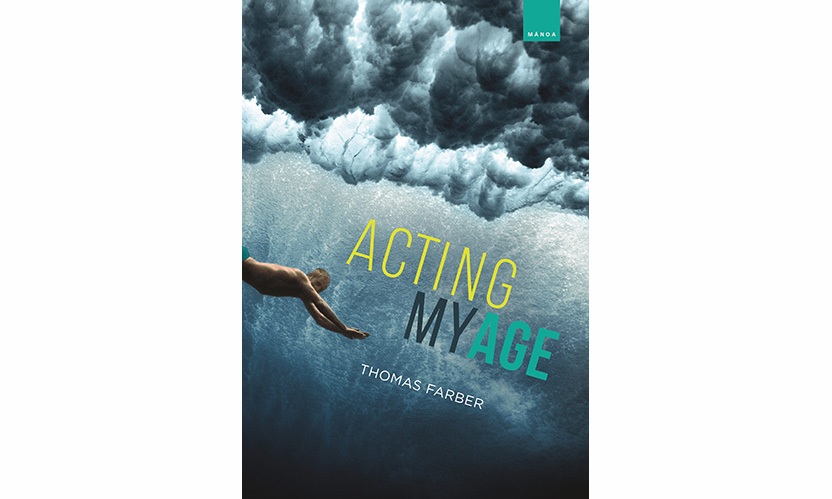

Thomas Farber’s Acting My Age

In Acting My Age, Thomas Farber reflects, with wit and insight, on his own mortality as well as on the impending extinction of vital presences in the natural world, from coral reefs to snow leopards. The author of over two dozen wide-ranging books of fiction, nonfiction, and epigrams, Farber teaches creative writing in the English department.

The following excerpt from Acting My Age includes Farber’s prefatory “Author’s Note” and his book’s postscript.

Author’s Note

Joseph Joubert (1754–1824) yearned to put “a whole book in a page, a whole page in a sentence, and this sentence in a word.” Despite—because of?—this ambition, Joubert never published any book at all.

About my own yearnings, author seventy-two to going on seventy-six, these pages seemed, variously, daily craft pursuit; house being constructed; mania; self-directed homeschooling; word music being composed. Also self-sentenced “hard labor.” Also life raft. Also, arguably, spiritual practice.

Less ambitious than Joubert, I was tempted—merely—to convey what I could about aging, the fate of the ocean, our political moment, the writing life, family, and words. Meanwhile, there were sections revised but recalcitrant. Mulling if I should wait for laggards, I hoped to stave off a posthumous publication date. What’s here, then, is an interim report. Work in progress for the meantime / meanwhile—like the currently ongoing self.

Readers will see I address my concerns repeatedly from different points of entry. Repetition compulsion? Tenacity? You’ll decide. (Poet James Merrill: “It’s madness to think of an audience. It’s madness also not to think of one.”)

Meanwhile, something less abridged soon? Years ago, an opinionated fellow—aesthete without an art, is how I came to think of him—told me I’d never stop writing. Never—n(ot)ever. Since he’s “no longer with us”—silenced by his own hand—we’re unable to further discuss whether or not he was correct.

Demos (Latin), “the people.” In early 2020, as I did last revisions, epidemic became pandemic. Epi, “among.” Pan, “all.” Here, then, you’ll find nothing about the heroes, victims, benedictions, or maledictions the virus elicited. Survivor-reader you, hopefully disembarked from the infected ship of state on which we were trapped, might even read this in a post–COVID-19 world.

Reverted to ordinary life? If so, what new normal? Except for victims and loved ones, wars and plagues seem too soon left behind. Life for the living! After prophylactic hand-washing and wringing of hands, we’re to emerge transformed? Or, as sleepwalking / mind-infected Lady Macbeth put it, “What, will these hands ne’er be clean?”

In his very last poem, Jim Harrison wrote, “Man shits his pants and trashed God’s body.” With luck, in the de-quarantined post-pandemic, those of our squabbling, bickering kind who’ve been spared will better care for other members of our species. And/or, will do more to save the rest of Creation from us. Meanwhile, some of my writerly obsessions the five years before epi became pan may shed light on the madness that ensued.

—Thomas Farber Berkeley and Honolulu March 2020

Postscript: Late March 2020

William Wordsworth, two centuries ago: “Little we see in Nature that is ours; / We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!”

Just after sunset, pulsing fist of Venus in the west. Close to the waxing crescent moon. Seemingly close: Venus, 84 million miles away; our reliable “natural” satellite a within-reach 240,000 miles.

Earthshine, sunlight reflected from this blue planet, illuminating what appears—to us—the otherwise unlit portion of the moon.

Bob Dylan:

“Things have changed.”

“It’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there.” “A hard rain’s gonna fall.”

Northern California spring, pandemic hyper-bloom. Hyper-busy no-nonsense bees making their own kind of hay while the sun’s high. Zero to twenty mph in a millisecond. Stunt pilots swooping toward you as they head to the hive, veering away at the last possible instant.

A butterfly alights. Basks: solar recharge. Wings lifting and falling very slowly, as if catching their breath.

Placard in neighbor’s window: in our America love wins.

More than forty years ago, Three Wanderers from Wapping was published, my mother’s adaptation of an episode from Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year. Illustrations by Charles Mikolaycak, corpses and rats vividly rendered. For the young of all ages, as my mother thought of such projects. For “ages: 10 & up,” as the publisher marketed it.

“It was the summer of 1665, and the plague was raging in London,” my mother’s tale begins. Gatherings banned, the only open business “that of tending the dead and the dying.”

And, my mother wrote:

“It is hardly surprising that in the midst of all this disease and dying, many folk turned to the scores of mountebanks and wizards who promised protection or cure—or at least knowledge of the future—by a thousand outrageous methods. Fortune-tellers read cards and tea leaves. Astrologers interpreted the stars. Conjurors and quacks sold multitudes of pills, potions, and preservatives, as they were called. The pitiable folk wore all sorts of charms and amulets to fortify their bodies against the plague.”

That was there and then. Here in the cottage, it’s five a.m. Venus and crescent moon absenting themselves till evening. Town stiller than still. Deathly quiet.

And those who have a home? Sheltered in place. Home / bound. Waiting to learn who the virus took, spared.

Excerpted from Acting My Age, published by University of Hawaii Press. Copyright 2021. Used with permission.