In memory of Professor Donald Friedman

This memorial for our beloved colleague Donald Friedman, who died early this summer, is offered by three of his former students: Kimberly Johnson, Michael Schoenfeldt, and Kate Levin, with contributions from his wife and two sons.

There will be a memorial service for Professor Friedman at 2pm on December 13, 2019, at the Women’s Faculty Club. For more information, please email donfriedmanmemorial@gmail.com.

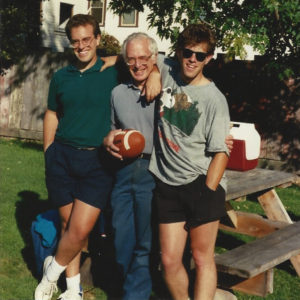

Professor Emeritus Donald Friedman died on June 10, 2019 of respiratory failure. He is survived by his wife of sixty years, Stephanie, and his sons Elliot and Gabriel.

Professor Friedman was born in the Bronx in 1929, and raised in Brooklyn and Woodmere, Long Island. As a ten-year-old he rode the subway alone into Manhattan to attend the “gifted” program at P.S. 208, where he was among those students recruited to appear on NBC’s “Quiz Kids” Radio Show (he fondly recalled walking in on Arturo Toscanini rehearsing the NBC Symphony). He also attended the legendary Townsend Harris Hall High School, where he first began to consider a teaching career.

Friedman received his B.A. in English from Columbia College in 1949, studying under Lionel Trilling, Mark Van Doren, and Jacques Barzun, and with F. W. Dupee, who was a welcome and revered influence on the young undergraduate. Friedman credited the Core Curriculum as key to his intellectual development—he often claimed to be able to spot a Columbia alum after a few moments of conversation—and remained devoted to Columbia throughout his life.

He was awarded a Henry Fellowship for a year’s study at Trinity College in Cambridge, England. One year became four as he pursued a Masters degree and a second B.A. in Philosophy, as well as more informal research into British theater, humor, country walks, and pubs. He retained a love of England and its people, returning there twice with his family for extended stays.

After returning from his studies in England, Friedman was drafted into the army for two years, one of which was spent in Japan just after the Korean War. He fell in love with Japan, and, like all of his attachments, this one lasted all his life. At the conclusion of his Army service, Friedman pursued a Ph.D. in English from Harvard, completing it in three years before accepting what became his career-long appointment in the English Department at the University of California, Berkeley.

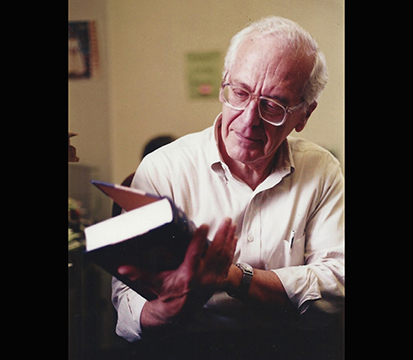

For decades, Professor Friedman’s gemlike investigations into Renaissance poetry and drama dazzled readers with their clarity and integrity, as well as their capacity to refract a bewildering variety of concerns. He has had the enviable distinction in his scholarly career of writing the single best essay on a variety of signal figures and poems. His series of essays on Thomas Wyatt from the early 1960s are still the finest sustained discussions of that important and elusive figure. He edited a facsimile edition of the Otia Sacra of Mildmay Fane, the Earl of Westmorland, which at its 1648 publication represented the first poetic foray into print by an English peer. Friedman’s edition of Eldred Revett’s poetry continues to offer modern readers their only opportunity to engage with the works of this seventeenth-century writer. And his monograph Marvell’s Pastoral Art has aged beautifully; its quiet knowledge of the ways that history presses on the act of poetic composition predates but also transcends the more recent turn to politics in literary criticism, and its profound awareness of the way that genre functions historically produced some remarkably fresh, and theoretically prescient, interpretations of this elusive poet.

Throughout his career, Friedman’s work exemplified a careful attentiveness to literary texts, which he combined with a nuanced understanding of political, religious, and cultural contexts. His splendid essay “Comus and the Truth of the Ear” demonstrates the ways in which Milton’s masque tests its audience’s ability to discern “true” meaning through the bosk of slight linguistic variation, and suggests that the masque’s high incidence of neologism amounts to a verbal trial of faith. This notion recurs in “Donne, Herbert, and Vocation,” which details the interpretive labor required to detect the voice of a silent God through the texts of the world and the self; the paper was recognized as 1995’s “Distinguished Publication in Donne Studies.” In “Lycidas: The Swain’s Paideia,” Friedman traced the ethical development of the shepherd who speaks the poem by recording the cogency and authenticity of various literary conventions of mourning. And in his magisterial treatment of Donne’s “Goodfriday 1613,” Friedman understood the poem as enacting a renovation of sight from mere visual perception to a faculty that relies instead on the soul’s “inner eye of memory.” Yet once more, Friedman explored a text in which transformation is available, but only through an engagement with signs that is both intellectual and visceral, rigorous and pleasurable. Throughout his remarkable career, Friedman practiced a profoundly ethical criticism, in which compassionate and scrupulous attention to the provocations and gratifications of literary texts produces models for textured engagement with the world.

Professor Friedman was admired by his colleagues for shouldering significant service responsibilities with characteristic gentle good humor and graciousness. His appointments as Chair of Berkeley’s Department of Dramatic Art and Dean of Humanities indicate the interdisciplinary respect he enjoyed, cultivated over long years as a dedicated university citizen—reflected not least in his herculean (and frankly unglamorous) service on the system-wide Budget Committee. Friedman was recognized for his distinguished service by the UC-Berkeley Senate Divisional Council in 1994-1995, and in 2000, he received the Berkeley Citation, awarded to a distinguished individual whose contributions to the university go beyond the call of duty and whose achievements exceed the standards of excellence in their fields. He received Berkeley’s highly competitive Distinguished Teaching Award twice; the two decades that passed between his two awards signal his unflagging and generous commitment to his students.

Indeed, from his arrival at the University of California-Berkeley in 1961 until his retirement in 2001, Friedman stoked enthusiasm for Milton, Shakespeare, and the lyric poets of the English Renaissance in undergraduates and graduate students alike, winning many of them to professional specializations in the field. Doctoral students fortunate enough to have him direct dissertations were encouraged by his standard of painstaking research combined with magnanimous grace, and by his undisguised appreciation for the subjects of study. Students praised the breadth of his learning: As one student wrote in a course evaluation, “His knowledge is astonishing and he communicates it with such ease and grace….His commitment to relating the literature that we read to the political situation, ecclesiastical history, art history, and architecture was wonderful. This is my favorite approach to the study of English, and one that is surprisingly rare.” “Being in his class is a constant reminder that literature is a joy,” according to a student in another graduate course. But Professor Friedman’s mentoring went beyond pushing his students to produce high-quality scholarly work; he remained for many of his former students their most important reader, generously but vigorously vetting anything sent his way. Michael C. Schoenfeldt, John R. Knott, Jr. Collegiate Professor of English at the University of Michigan, finished his dissertation under Professor Friedman’s direction in 1985; he remembers Don’s generous openness to the new modes of criticism that were sweeping the profession, as long as they were wedded to an unconditional investment in scholarly rigor. Kate D. Levin, who finished her dissertation in 1996 and held a joint appointment in the departments of English and Theater at City College/CUNY before serving for twelve years as Commissioner of Cultural Affairs for New York City, recalls the extraordinary breadth of his curiosity: “Don modeled expertise as a way of knowing, not just a body of knowledge. He brought suppleness and imagination, alongside precision and thoroughness, to the decision-making that drives interpretation.” And BYU Professor of English Kimberly Johnson, whose dissertation Friedman supervised to completion in 2003, appreciates that his mentoring served the whole person, reflecting that “Through his manifest investment in my life outside the classroom and beyond the dissertation deadline, Don reminded me that the real magnitude of our shared pursuit of the Humanities is that it nurtures us to be humane, and to value the human.”

Beyond his scholarly pursuits—or more aptly as a complement to them—Friedman had a deep love of language and wordplay. While at Columbia, he was instrumental in reviving the old Philolexian Society, which at one point unwittingly awarded its third place prize in poetry to “Winslow Ammerman,” a fictional poet contrived by Friedman and his lifelong friend John Hollander, with whom he went on to conduct a perpetual correspondence comprised primarily of puns, allusions and other forms of verbal play. He also composed, for his own pleasure, more serious verse, poems that show the formal and thematic influence of the work to which he dedicated his life.

It was in England that he’d discovered a culture with a similar affection for language and its uses. He wrote of feeling at home among the English because of their fondness for and skill with storytelling and humor. Friedman delighted in finding people who also enjoyed verbal sparring and playful humor, and most of his closest relationships were sustained by this shared love of the English language, its oddities, and its beauty.

He also had an abiding love of music. He took immense delight in Stephanie’s career as a distinguished mezzo-soprano. He and Stephanie attended performances around the world, and they were frequent San Francisco Opera- and Symphony-goers. In his later years, Friedman fulfilled a long dream of taking piano lessons, and he would thrill to hear a familiar, if simplified, theme by a great composer emerging from under his very own fingers. It is not surprising that this lifelong passion, too, intersected with his fondness for Berkeley—for Professor Friedman had a hand in bringing world-class music to the Berkeley campus, having been intimately involved in the creation and success of what is now Cal Performances. After one particularly stirring program by the visiting Jerusalem Quartet at Hertz Hall, he turned to his son Elliot and said, “I need this like I need to breathe.”