“The Luckiest Person in the World”: In Memory of Professor Alex Zwerdling

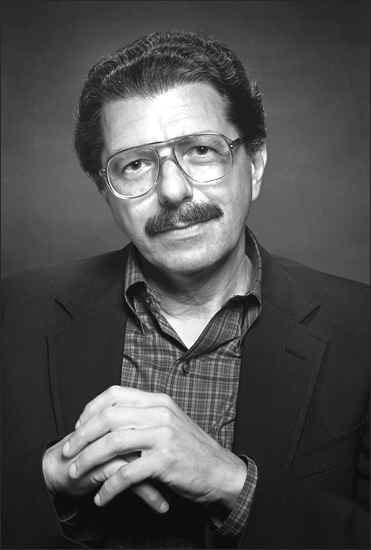

English Professor Alex Zwerdling passed away on May 16, 2017 at the age of 84. Author of five acclaimed books, including the just-published The Rise of the Memoir and recipient of Fulbright, Guggenheim, and National Endowment of the Humanities Fellowships, Professor Zwerdling joined UC Berkeley’s English Department in 1961. He was a key figure in shaping the department over the five decades he taught at Cal.

The Department will hold a memorial in honor of the life and work of Alex Zwerdling, on March 3, 2018, at 3 p.m. in the Maude Fife Room (315 Wheeler Hall). A reception will follow in 330 Wheeler Hall. All of Alex’s friends, colleagues, students, and others are invited to join us. Event Contact: 510-642-3467.

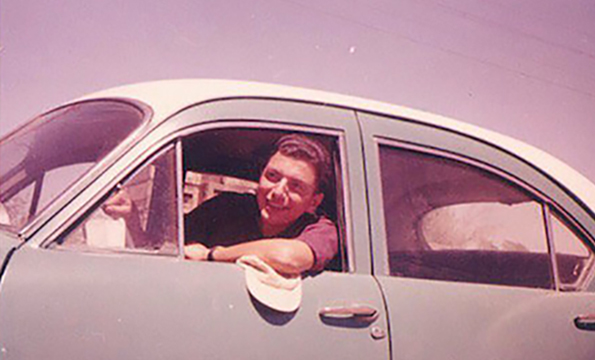

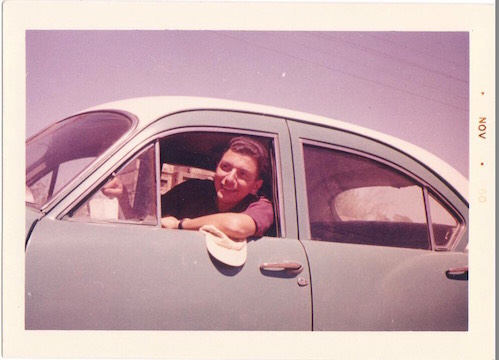

“I am the luckiest person in the world,” Professor Alex Zwerdling often noted, “because I get paid to do the things I love.” Incredulous when, as an undergraduate chemistry major at Cornell, one of his professors (the legendary scholar of Romanticism M.H. Abrams), let him know that some people make a living by reading and writing, he never got over his delight at discovering that he could be among them. For over forty years Alex shared that delight with students and colleagues at the University of California at Berkeley. After joining the Department of English as an Assistant Professor in 1961, he taught a wide range of courses on twentieth-century British and American literature until his retirement in 2002.

Alex devoted his scholarly career to expanding our understanding of the interplay between distinctive writerly voices and the social contexts in which they are developed and received. A prolific scholar who published five books and numerous articles on a range of twentieth-century British and American writers, he mapped the subtle pathways of individual careers across changing cultural and political landscapes. He relished the archival research that excavates the multiple drafts, inchoate projects, and uncensored correspondence that help to shape but never make it into a writer’s published work. A graceful writer and avid reader who succeeded in addressing a general public as well as literary scholars, he wore his extensive learning lightly and tempered his commitment to literature’s cultural complexities and complicities with a sense of humor and pleasure in the craft of writing. That pleasure lit up scores of classrooms and conversations in Wheeler Hall.

After receiving his Ph.D. from Princeton, Alex reworked his dissertation into his first book, Yeats and the Heroic Ideal (1965), in which he unpacks Yeats’ transformation of the Victorian hero from a figure of self-sacrifice to a model of self-fulfillment. The social pressures underlying this transformation assume a different guise in Alex’s second book, Orwell and the Left (1974), which nuances the received account of Orwell’s disaffection from the Left by reconceiving him as the Left’s “loyal opposition.” Alex’s breakthrough piece of scholarship was Virginia Woolf and the Real World (1986), which radically reoriented Woolf studies from a putatively reclusive author’s representation of consciousness to what Zwerdling characterizes as her “social vision – her complex sense of how historical forces and societal institutions influence the behavior of the people she describes.” Designated by feminist scholar Elaine Showalter as “the finest critical book on Virginia Woolf to date,” an accolade particularly striking during the heyday of feminist criticism, Virginia Woolf and the Real World has developed a life of its own, both as a text and as a tag phrase that reminds us to position unlike terms in relation to each other.

In his two most recent books, Alex turns his attention from individual authorship to collective literary experiences and genres. His magisterial Improvised Europeans: American Literary Expatriates and the Siege of London (1998) offers a rich exposition of the logic and consequences of the decision by four signal American writers – Henry Adams, Henry James, Ezra Pound, and T.S. Eliot — to leave the United States at the emergence of its cultural ascendance to become “improvised Europeans” in London. Most recently, The Rise of the Memoir (2016) charts the history of a genre whose current popularity has obscured a trajectory that starts with Rousseau’s unprecedented determination to “say everything.” Reaching from Rousseau’s Confessions through Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son, Virginia Woolf’s “Sketch of the Past,” George Orwell’s “Such, Such Were the Joys,” Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory, and Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz to Maxine Hong Kingston’s Woman Warrior and China Men, Alex tracks the erratic course of a constantly changing genre as it negotiates the tensions between self-disclosure and self-defense. After noting the discomfort that memoirs can inflict on their readers, Frances Wilson, who reviewed Alex’s book for the Times Literary Supplement, affirms that “The Rise of the Memoir, on the other hand, will be greeted with resounding applause.”

Alex’s devotion to Berkeley’s English Department across the five decades of his career assumed many forms. A natural teacher, he won praise from students in a wide array of courses for the scope of his knowledge, the depth of his preparation, and the lucidity of his presentation. One student called him the “best and most intelligently organized teacher in the department.” Among the department’s most sought-after doctoral advisors, Alex was well known for his meticulous reading of student writing, his blend of patient attention with rigorous critique. “He was endlessly kind, and patient, and funny,” as one of his graduate advisees put it. For another, his greatest gift was teaching by example how to teach.

Alex was also a supportive mentor for younger faculty members, each of whom he welcomed individually to the department: “he was the welcome,” as one of his colleagues recalled. Always eager to extend his understanding of diverse methodologies and fields of study, he sought out and fostered the distinctive interests of each new member of the department. He made a special point of encouraging young women who were entering the profession at a time when there were few in senior positions. For his scholarly distinction and many forms of academic service, both locally and nationally, he was awarded the Berkeley Citation upon his retirement in 2002.

It would be hard to imagine a better exemplar of the humanistic ideals that have come under attack from various directions in recent years. By embodying those ideals in his scholarship and teaching, Alex Zwerdling has given them a form that will outlive our shifting critical and political regimes.

– Elizabeth Abel, Professor of English