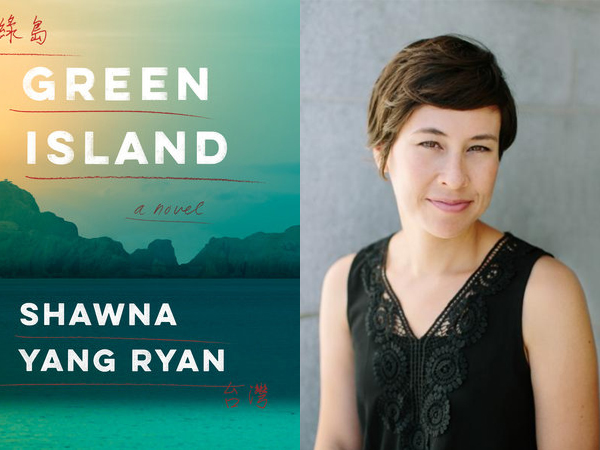

Robert Hass and Amanda Su interview author Shawna Yang Ryan

Earlier last year, alumni and author Shawna Yang Ryan (’98) published her second novel, Green Island, an exploration of immigration and 1940’s authoritarian rule in China through the narrative of one girl force to flee with her family to California after the The February 28 Incident in Taiwan. Recently, Professor Robert Hass and graduate student Amanda Su sat down with Ryan to discuss her writing process, her time at Cal, and the mentors and authors that have shaped her craft.

Robert Hass: The characters in Green Island, even the minor ones, are intensely vivid, a quality I associate with Tolstoy. I wonder how they emerge for you. Do you look at what you’ve done and add touches to bring the character alive, or does it not work in that self-conscious way?

Shawna Yang Ryan: Thank you. That’s quite a compliment. I can’t write a scene until it’s fixed in my mind like a memory, so I imagine I’m recounting what I’ve seen and experienced. I try to envision the people as if I’ve encountered them and heard them and watched them breathe.

Amanda Su: I’m also curious about how the idea for the novel occurred to you, which pieces of it fell into place first for you. Why were you drawn to this particular time and place? Did you always know that it was going to be from the perspective of a girl who was born on 228?

SYR: The novel started with my discovery of the 228 Massacre, because I didn’t hear of it until I was twenty-one, when I was living in Taiwan after graduating from Cal. I just happened into the 228 Memorial Museum in Taipei one day and I could not forget what I learned there. The idea for the novel came not long after.

But it was many more years until I could figure out how to tell it. Early drafts were in third person, and I was going off the rails a bit in terms of scope and spinning away from reality (there was a lot of outrageous fantastical stuff in one draft), so switching to first person was a way to rein it in, and delimit the story. At some point too I went from a really frenetic and dense voice to wanting something very straightforward, simple and traditional, which writing in the narrator’s voice allowed me. From there, I focused on the eras in her lifetime that I was particularly intrigued by—the 1940s, the 70s with the American presence, the 80s, and then SARS, which I was in Taiwan for during my Fulbright researching the book.

RH: I was really quite stunned by the description of the way KMT agents in the novel harassed and threatened Taiwanese graduate students in Berkeley in the 60’s and 70’s. Did that really happen? How did you come to hear about it?

SYR: Yes, that was based on truth! I heard about it in my interviews with Taiwanese Americans who had come to the US for grad school. It was a shocking revelation for me because at the time I had thought of the US as this untouchable and safe place where people would be free from the reach of their repressive homelands. Obviously, that isn’t the case. There are a few other true stories that influenced the plot, one being the story of Henry Liu who was murdered in his driveway in Daly City by men hired by the KMT. However, the real life case received a lot more attention by the American media than the similar incident in the novel does.

AS: I know that you did a great deal of interviewing and digging through books and archives for this project, so from a researcher’s standpoint — when do you know that you’ve gathered enough material, when do you know where to stop, and how do you determine where your narrative is going to diverge from the accounts you’ve collected? I’m struck by how vivid and detailed your writing is — what was playing on the radio in Taiwan in 1947, the things that people sold on secondhand markets, what items were imported from Europe — how did you go about collecting these details? Which parts of the novel were most difficult to write, for reasons of plot or periodicity?

SYR: Sifting, sifting, sifting! I went through huge amounts of material for just a few great details. It wasn’t very efficient! By being immersive, I could just gather details here and there. For example, I went to a Taiwan film fest in SF and watched a film about the 1940s music industry in Taiwan, where I picked up the details of what was playing on the radio, and that the record players had bamboo needles during the war. So I tucked that away for possible future use. Finding details that way takes a lot of time because it depends so much on serendipity. I’m not sure you can go looking for those things. Even now, with the book published, I still hear tidbits and think: I wish I could have added that! So it’s hard to turn off the research brain.

Each period relied on different kinds of research. The 1940s section was more text based research, with oral interviews, while by the 1980s, many of my interviewees had already immigrated, so I relied on my own memories of visiting Taiwan, films, and old family pictures.

The 1950s section was most challenging, mostly because of the positioning of the narrator, who is a child at that point. The entire novel is told from the point of view of the adult narrator recounting her life, so there was this tricky balance between those two narrative consciousnesses of the child and adult, to convey the innocence of the child against the knowing hindsight of the adult.

RH: Has Green Island been translated and published in Taiwan? What kind of reception did you get or do you expect?

SYR: The translation will be released in November in Taiwan and I’ll be there to do some press for it. I’m not sure what to expect—the Taiwanese American community has been extremely supportive, and I’ve had a few interviews with Taiwanese who read English who have also responded very favorably, but I’m curious to see how the novel reads in Chinese, if English covers up some of the tonal/historical flaws. Also, there are still, surprisingly and unfortunately, some 228 Massacre deniers, so I expect there might be some pushback from that faction. Whatever happens, I’m excited and ready!

AS: This question is partially based on a personal observation about Asian American writers ranging from Maxine Hong Kingston to Amy Tan — there’s a tendency to illuminate certain phrases in Mandarin by referencing their literal translations into English — the characters for the phrase “grammar,” for example, is “word law.” But I didn’t notice any of that in your novel, which made the atmosphere of the languages invoked in it feel more real to me (a native speaker probably wouldn’t stop to consider that “grammar,” when broken down, constitutes the characters for “word” and “law” — the phrase has already been assimilated as a whole for them, the way that an English speaker would not necessarily reflect upon the Greek or Latin roots of commonplace words).

Was it thorny or difficult to write about Taiwanese people, to render dialogue that was supposed to have been delivered in Taiwanese or Mandarin, in English instead? Did you ever feel like a translator, of sorts?

SYR: Translation is a good way to think about it. I know there are many different theories on translation, and for me, the role of the translator is to render the home language natural in the target language, so that the translation is undetectable. So I was working with the assumption that we were fully inhabiting the narrator’s mind and language—what does it sound like from inside that space? I wanted it to be as natural as it would feel to her. Examples like the one you offer can feel alienating, and I didn’t want—couldn’t—make the narrator’s world feel exotic—to her or the reader. I don’t think it was necessarily “thorny,” but I was conscious of moments when I could have gone literal to offer some “flavor” and resisted.

I wish I had integrated more of the diverse linguistic and cultural landscape of Taiwan. I didn’t have a Hakka character, and I should have. As far as the linguistic palette—it came from listening to my family in Taichung speak, or people on the street, and how they code-switch all the time. Taiwanese and Mandarin were strictly divided at one time, with Taiwanese forbidden—and schoolchildren even punished for speaking it—but in contemporary Taiwan, the languages seem to have become intertwined. I hope I’ve captured some of that.

RH: If the girl you were were a character in a novel, how would you describe her when she entered Berkeley?

SYR: Hungry to leave Sacramento. Eager to be an adult, even if it meant making questionable decisions like getting her nose pierced at a table on Telegraph the first week of school. Awkward, in oversized men’s clothing, the Ally Sheedy character in The Breakfast Club. Self-consciously absorbing the “college experience” (“Now, I will write my participant-observation cultural anthropology essay on dancing at frat parties”). Didn’t know how much she had yet to learn!

AS: Like Bob, I’m curious to learn more about your time at Berkeley and what kind of a place it was for you, how it might have shaped your writing. And I know this is a bit soon to ask, since Green Island came out just this year, but are there other projects you have planned? Are there other things you’d like to mention that we haven’t asked about yet?

SYR: I’m into some research about a novel concerning the Los Angeles Aqueduct, but it’s early days yet. I’m also very slowly working my way through a translation of a Taiwanese author.

RH: I would estimate that about half the writers who majored in English at UC Berkeley have said that it nourished or inspired them and about half did not have such friendly things to say. Where do you come down on you experience as an English major?

SYR: I loved Berkeley! I truly did. I remember my time there as invigorating. I felt I’d stepped into this much larger world. Getting to hear writers like Adrienne Rich and Maurice Sendak who came to read was magical. I had the great fortune to take writing workshops with Ron Loewinsohn, Tom Farber and Maxine Hong Kingston, and what I learned from them still resonates today. My experience as an English major was really formative, and I still am friends with quite a few of my workshop classmates.

RH: I know that Gary Snyder really admires your work. Was he helpful to you at UC Davis? How so?

SYR: Gary was and continues to be a generous mentor and friend. He was the first person I encountered in my academic journey with whom I could talk about Chinese poetry and history. He pointed me towards readings, offered me access to his library, and also provided a very balanced view of what it means to be a writer. When I’m feeling frantic and anxious about this pursuit, I hear Gary’s calm voice. I find myself often reoriented and grounded by his outlook and wisdom. I had the great fortune to interview him for the Asian American Literary Review, and this advice stays with me:

“So as an artist, how do you live your life? Well, you live your life quite broadly and quite openly to paying attention or taking cognizance of little things on the margins as well your mainstream focus. . . as much is happening on the edges as is happening right in front of you. Don’t be totally obsessed.”

—–

Shawna Yang Ryan is a former Fulbright scholar and the author of Water Ghosts* (Penguin Press 2009) and Green Island (Knopf 2016). She teaches in the Creative Writing Program at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa. Her short fiction has appeared in ZYZZYVA, The Asian American Literary Review, Kartika Review, and The Berkeley Fiction Review. She is the 2015 recipient of the Elliot Cades Emerging Writer award. Originally from California, she now lives in Honolulu.

*1/5/17 Editors note: After the publication of this piece, we were contacted by English Department Senior Lecturer and multi-award winner Thomas Farber with an interesting story: in 2005, Shawna submitted the manuscript of her first novel to Professor Farber’s nonprofit publishing house, El Leon Literary Arts. El Leon gladly took it on, publishing it in 2007 as Locke, 1928, Shawna’s chosen title. Shortly after, Penguin picked up the book, changing only one thing, the title (to Water Ghosts).