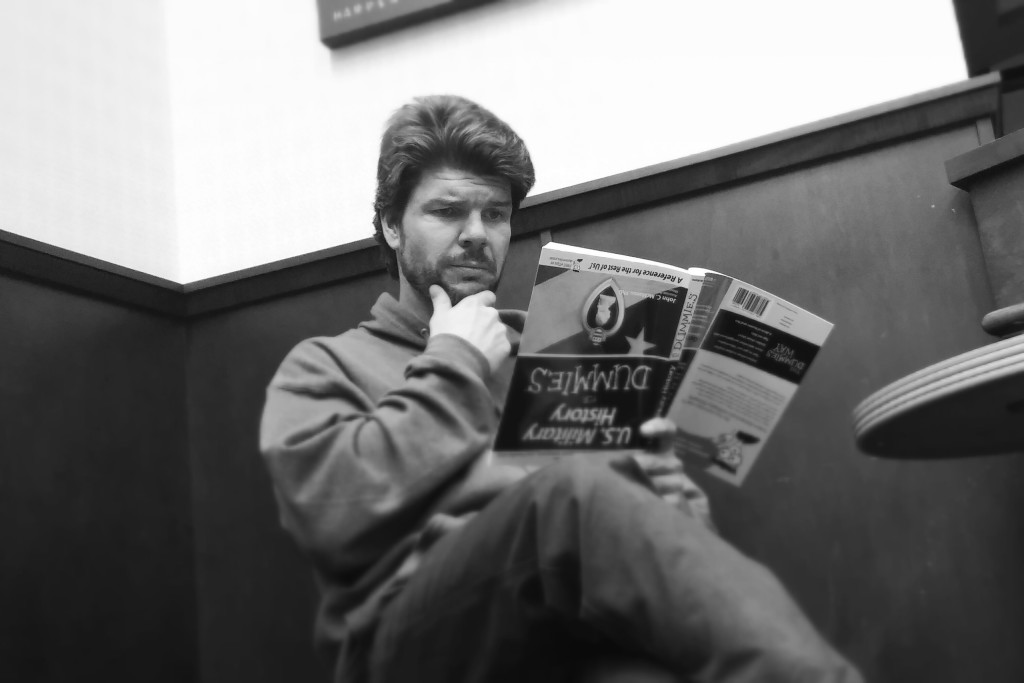

Undergraduate Voices: Steven Czifra reflects on the pull of activism and academia

The following article was written by Steven Czifra, an English Undergraduate transfer student. The piece is a reflection on reconciling his “past as a formerly incarcerated person,” with his “new life as a Berkeley English undergrad” upon transferring into the Department.

Steven has won multiple campus awards, including a 2014-2015 Hass Scholars Humanities Fellowship for his work titled, “Emerging Discourses in California’s Solitary Confinement Debate.” He will graduate this Fall 2015 semester.

In the spring of 2013, my first as a Cal undergrad, I was invited to help with the effort to raise awareness of a California prisoner hunger strike that was set to begin in July. The thousands of men and women in the state’s SHUs (Security Housing Unit, where people were kept in isolation for decades) were protesting to get things like food, education, and due process of the law. My first semester at Cal completed, I was aware that being an English major at UC Berkeley was going to be challenging. I realized I could do myself a favor and focus on the job of being an English undergraduate. It was what I wanted to do: being in classrooms and libraries all day with people who were experts, or trying to become experts in literature, and studying great works of art was a dream. Advocating for prisoners, on the other hand, was not pleasant and did nothing to facilitate my own plans of becoming a literary scholar. My struggle was with finding a way to reconcile my past as a formerly incarcerated person, having spent eight years in a solitary confinement cell in both youth and adult prisons, and my new life as a Berkeley English undergrad. Students at Cal hunkered over the same texts–the Aeneid, Odyssey and The Inferno, Richard II and Paradise Lost– in the Doe Library, or behind coffees at the Free Speech Café, that I had pored over in a very different setting, a cloister without the salve of promised redemption, a California solitary confinement cell. What had I now to do with a bunch of hungry prisoners in the Pelican Bay, and Corcoran prison lockdowns? I was at the best English department in the world, at the best university, and a world away from that other reality. I had a decision to make. I struggled with my decision for only a short time before deciding in favor of participating in the effort to amplify the silenced voices of the prisoners.

I equivocated for a few minutes. Less, probably. Knowing what I knew, the worlds of suffering inside each of those cells, cut off from all of humanity to satisfy some bureaucrat’s need for revenge, I could not say “no” to the offer to be of service to these people. In the end the hunger strike lasted for sixty days, with many of the strikers suffering great physical harm, and one, Billy “Guero” Sells, dying.

In the spring of 2015 I was given the Chancellor’s Award for Civic Engagement because of my efforts on behalf of the strike. I had been traveling with my family–my then six year old son Shane, and partner Sylvia Garcia–around the state to various prisons, the three of us, alongside dozens of activists and family of the prisoners, drawing public attention to the otherwise silent protest inside the prisons. After the strike ended, in 2013, I was invited to a state hearing to tell the Public Safety Committee what it meant for me to have been in solitary confinement. My message? It hurt. This was also the message I carried to many other audiences, in churches and university classes, Rotary lunches, and a dozen or so media outlets. On every occasion, I emphasized not only the pain of isolation, but the lasting effects of being deprived of human touch, or any human interaction not mediated by the bullet proof glass, and often faulty telephone receivers of the SHU visiting booths.

After such experiences, and with the continuing cruel punishment of so many thousands still incarcerated in the state’s SHUs, I wondered: how could I accept an award that commemorated so much suffering, and the civic engagement of so many people besides me? I realized I could not refuse it. The tiny part I played in the strike was continuing to create a platform (such as this blog post) for the discussion that the strike had started. That award now sits in my living room, a reminder that there is still widespread solitary confinement for thousands of people across the state. The award also reminds me that as an alumnus of the Berkeley English department, I can speak more forcefully, and to wider audiences, about my status as a formerly incarcerated person. My presence in academia is thus not separate from the “me” that struggled in the past with day-to-day life in prison. Besides, it was really only luck, and the ability to follow directions from wise community members that, together, have brought that same person to Cal.

Today, you can find me at the Underground Scholars Initiative (USI), a UC Berkeley student-led program that is working to create greater opportunities for formerly incarcerated people to come to Cal, and for them to find a community when they arrive. While the hunger strike is not directly linked to this work, the 30,000 California prisoners who put their safety on the line in the early days of the strike, the forty-plus men who persisted for two months without food, and the countless community members who have since spoken against long-term isolation have helped to bring that conversation to Cal, and it is that conversation that in great part brought us Underground Scholars together.