Undergraduate Research: A Diegetic

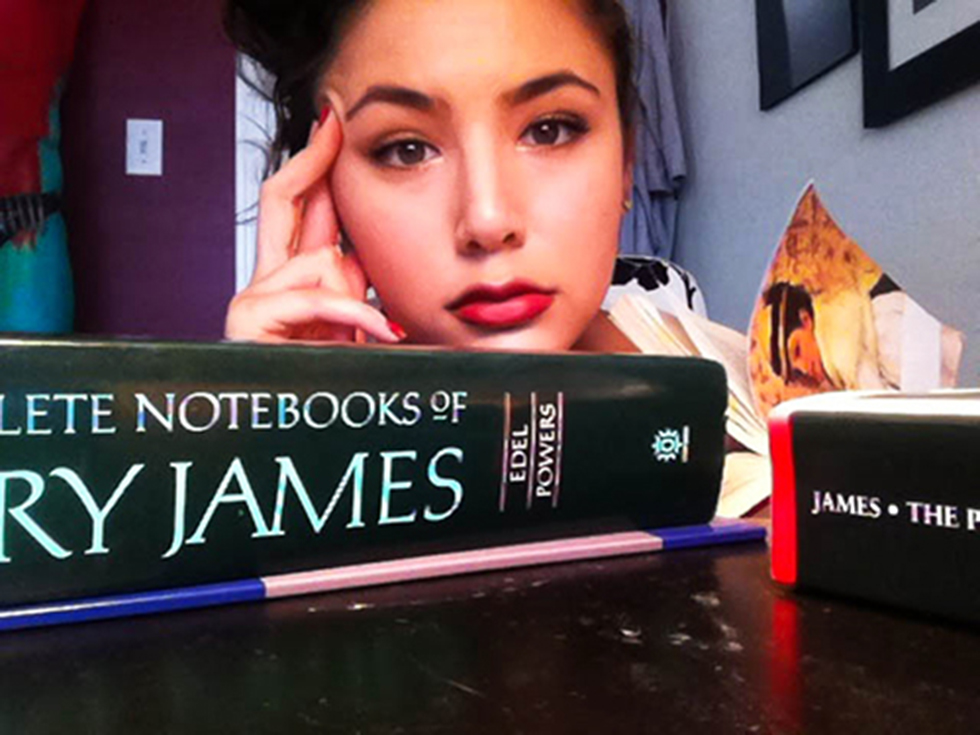

In the following article, Emily Doyle (’14) considers the subject of her summer 2013 undergraduate research fellowship concerning Henry James and the phrase, ‘As if’. Emily will graduate from Berkeley this spring and is currently in the final stages of developing her research into an honors thesis focusing on the specific ways elements of fiction, grammar, and philosophy converge upon the phrase, ‘as if,’ in James’ What Maisie Knew, In the Cage, and The Pupil.

I’d like to tell you (the general “you” is an awkward thing to use, but you know who you are) about my summer undergraduate research fellowship and, in fact, I will. But first, an excerpt from Henry James’ What Maisie Knew (read slowly):

He never said a word to her against her mother — he only remained dumb and discouraged in the face of her ladyship’s own overtopping earnestness. There were occasions when he even spoke as if he had wrenched his little charge from the arms of a parent who had fought for her tooth and nail. This was the very moral of a scene that flashed into vividness one day … (77, emphasis added).

As you have undoubtably noticed, I have italicized two words in this sixty-eight word excerpt, and very small words at that: ‘as’ and ‘if’ which together form the phrase “as if” — grammatically, a double conjunction; narratively, a point of emphasis; philosophically, so much.

I spent my summer and now dedicate my senior honors thesis to this little phrase and looking into what it does in selected novels of Henry James — particularly, What Maisie Knew, In the Cage, and The Pupil. But, why (the inevitable question) concern myself with ‘as if’; and why look for it specifically in the work of Henry James? Well, several reasons — two of which I will discuss now: first, ‘as if’ is a double conjunction; therefore meaning will lean upon this phrase from both sides of the sentence (in the words prior and post). For evidence, let us (we know who we are!) review the precious excerpt, specifically the sentence in which ‘as if’ appears: “There were occasions when he even spoke as if he had wrenched his little charge from the arms of a parent who had fought for her tooth and nail.” In this sentence, a little girl named Maisie thinks (I base the idea that it is her thinking on the intimate status Maisie, as a character, holds in relationship to the narrative; that is, there are indications that the narrative limits itself largely to Maisie’s consciousness such as a general orientation of observations toward and around Maisie. This, of course, is the by now well-established “stream of consciousness” style James is so famous for; but why take anything for granted?) about the attitude her stepfather has adopted concerning her abusive and neglectful mother. The side of the sentence before ‘as’ contains a remembrance about something that had occurred, a real event in which “he even spoke”. The other side, the side after ‘if’, bears the impression speaking gave: that her stepfather had gone through great trouble, had indeed “wrenched” Maisie from her mother. However, between the speaking and what the speaking ostensibly communicated appears “as if”. What does its intrusion mean? Why doesn’t the text simply read, for instance (I am loath to rewrite but will do so anyway), “There were occasions when he spoke about how he had wrenched his little charge …”? I don’t think I have to keep asking these questions. I think you know. That is, you’re aware of the fact that ‘as if’ here doesn’t indicate Maisie’s remembering knowledge she has gained about those adults around her, but, rather, indicates a conscious struggle on Maisie’s part to grapple with the apparent falsity of that knowledge, with the fact that her trusted stepfather is saying something which doesn’t make sense to her as yet unformed mind and, therefore, appears ‘as if’. What a smart fictional girl.

So, you see, the grammatical placement of the double conjunction, ‘as if’, within the sentence connects what could be an observation of a truth/fact and, at the same time, troubles the very basis of the observation. It is quite exciting! But, as I said, that’s just the first part. As promised, here is the second (and I will go more quickly now): ‘as if’, as I formerly suspected and have now found, implicates a certain philosophical work within the text concerning the boundaries of reality. I amuse myself as I write this, knowing full well as I do so how ideologically burdened this word, ‘reality,’ is; and that many readers will have likely labored over this very term probably through the process of deconstruction, coming inevitably to the realization that it has indeed been constructed (consciously and unconsciously, through human and nonhuman means alike); and that by using it now, in this manner, I invoke a whole history of more brilliant work. Yet I cannot avoid it. ‘As if’, as the phrase appears in Henry James’ novels, forces the issue of reality (what is) and, with it, unreality (what is not) obtrusively into view.

And now to explicitly state the formerly implicit: Maisie, as indicated by the particular use of ‘as if’ in this excerpt, in an ironically real sense finds unreality. That is, she, using the clue of her stepfather’s silence concerning her mother as well as the apparent “dumb and discouraged face” he wears in her presence, and detects an inconsistency between what he says about her and what he says about her. His words indicate that he nearly had to force Maisie’s mother to put Maisie in his care; whereas his actions indicate differently. Now, it would be easy to claim that neither ‘saying’ is superior: that both actions and language are forms of artificial construction; however, common sense (a simultaneously useful and unpopular tool) reveals this is not the case. Maisie knows about her stepfather as he is and she also knows that this knowing doesn’t agree with a knowing that is being fed to her; that is, her relation to reality as well as the reality she internalizes simply cannot coexist with the images of reality and self her stepfather attempts to impose. And with that, ‘as if’ carves out from society the act of lying. Which is very interesting. It’s all very interesting. Particularly that, if nothing else, what ‘as if’ shows us is that we (all humans!) need mechanisms of fiction in order to begin to gain understanding. We need problematic phrases and troubling grammar; we need books and the imagined struggle of little girls; and we need to understand why we need all this. Something in you, I know, responds to this because something in me does too. And this response, in its total uniqueness, reaches an internalized chord of commonality.

Anyway, now that I’ve succeeded in fully giving way to a tendency toward self-indulgence and over-reductiveness, I’ll conclude. But before I do, I must move away from my address of the general you to one of a specific you — particularly, the undergraduate you who might want to participate in research at UC Berkeley. And to this person I simply say, do so. If I haven’t scared you off with abrasive, unrelenting enthusiasm it probably means you have either hated everything I’ve said and want to write a lengthy rebuke in response or are intrigued and still want to write a lengthy rebuke in response; either way, you have something to say and the University might very well give you money for simply acting upon your desires as it did me; and/or, better still, you might be provided with an opportunity to work with a frighteningly brilliant professor like my advisor, Professor Altieri. Good things await you.